“Bhikkhus, develop concentration. A bhikkhu who is concentrated understands things as they have become.”

SN 35.99

The concept of samādhi, derived from the Pali terms sam + a+dhi meaning “put together” or “collected,” is a state of mental unification or composure that is central to Buddhist meditative disciplines. This state can manifest in various forms, from the tranquility of śamatha to the clarity of insight meditation, highlighting its versatile role in the path to enlightenment. While commonly defined as a state of meditative concentration, Bante Punnaji Maha Thera convincingly, to me at least, in discussion of the Seven Factors of Awakening (satta bojjhanga), argues that a better translation would be ‘state of mental equilibrium’.

Samādhi is notably diverse in its applications, from being referenced with regards to walking meditation (AN 5.29) to the contemplation of the five aggregates and the four foundations of mindfulness (satipatthanas), illustrating its broad relevance across different meditative practices. The Buddhist discourses, particularly the Aṅguttara Nikāya and the Saṅgītisutta, elaborate on different types of samādhi, such as those leading to calm abidings through the jhānas, knowledge and vision through the perception of light, mindfulness and clear comprehension by contemplating the arising and passing away of feelings, perceptions, and mental fabrications, and the ultimate goal of destroying the āsavas –mental defilements or karmic vectors that condiction the grasping through which samsāra is perpetuated.

The Saṅgītisutta furthers elaborates on the nature of samādhi by distinguishing between empty, signless, or desireless concentration, with each type associated with specific insight developments like not-self (anattā), impermanence (anicca), or unhappiness (dukkha). The commentary on these distinctions emphasizes the importance of samādhi in developing deep insights based on one’s focus during meditation.

The Saṅgītisutta and other texts also describe samādhi in terms of its concentration levels, including those with 1) initial and sustained application of the mind; 2) without initial but sustained application; and 3) without both, illustrating the gradations of mental absorption.

| Samādhi Levels | Preceding | First Jhāna | Second Jhāna | Third Jhāna | Fourth Jhāna | Fifth Jhāna |

| Initial & Sustained | 𝄘𝄘𝄘𝄘𝄘 | 𝄘𝄘 | ||||

| Without Initial but Sustained | 𝄚 | 𝄚𝄚𝄚𝄚 | ||||

| Without Both | 𝄛𝄛𝄛 | 𝄛𝄛𝄛 | 𝄛𝄛𝄛 |

This nuanced approach is further explored in the Abhidhamma, which presents a schematic classification of the jhānas, aligning them with the broader spectrum of samādhi states, although not without controvery. But that we will explore further another day.

The Visuddhimagga adds another layer of distinction by differentiating between mundane and supramundane samādhi, access concentration, and absorption proper, highlighting the progression from preliminary stages of mental unification to deeper states of meditative absorption. This progression is marked by a shift from intermittent cognitive activity to sustained periods of pure cognition, a hallmark of deep samādhi.

Samādhi’s role is further elaborated on in the Dasuttara Sutta in the context of the gradual path of training, where it elaborates on the forms of concentration conducive to decline, conducive to stability, conducive to distinction, and conducive to penetration.

| Samādhi Form | First Jhana | Second Jhana | Insight |

| Generates Decline | ䷀ | ||

| Generates Stability | ䷀ | ||

| Generates Distinction | ䷀ | ||

| Generates Penetration | ䷀ |

The Iddhipādāsamyutta presents another angle on the topic of concentration through its discussion of the four roads to psychic power (iddhipādā). The four roads share common need for effort and will power but are distinguished by the type of concentration demanded.

| Four Roads | Notes |

| Desire to act (chanda-samādhi) | Concentration as consolidated through a powerful desire directed toward the goal of awakening, the eradication of the higher fetters, or the attainment of spiritual power. |

| Strength (viriya-samādhi) | Concentration is gained through an exertion of effort and energy to achieve the goal of practice. Skillful and diligent effort is applied consistently and appropriately, neither too forceful nor too lax. This balancing act of sustained and dedicated effort overcomes obstacles, cultivates wholesome factors, and maintains our achievements. |

| Inclining the mind (citta-samādhi) | Concentration is achieved through a natural purity of consciousness that is unified and undistracted in its orientation toward the goal. |

| Investigation (vimaṃsā-samādhi) | Concentration is obtained by sustained and penetrative investigation that discerns mental and physical phenomena as they are actually occurring. This concentration arises by contemplating the changing, unsatisfactory, foul, or empty nature of things, or through the careful examination of causes and effects. |

In order for such powers to be developed, the samadhi factors themselves need to be strengthened. The gradual path of training samādhi is built on the foundation of virtue (sila). From there, restraint of the sense-doors to overcome sensory distraction and attachment, contentment to not seek out distraction and sense-pleasures, moderation in eating to avoid drowsiness, and the development of mindfulness and right effort. These preparatory practices facilitate the overcoming of hindrances and the cultivation of deeper levels of concentration, leading to joy, tranquility, and ultimately, equanimity and a purity of mindfulness dropping pleasures and suffering (adukkhamasukha).

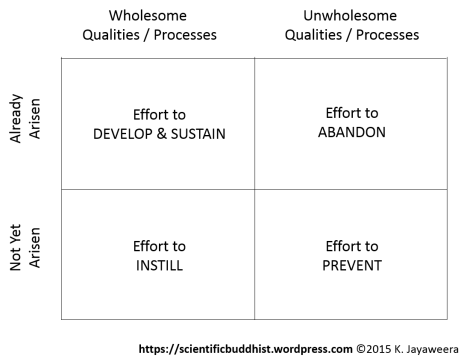

The Cūḷavedallasutta makes clear that there are requisites or tools (parikkhāra) needed for the development of samādhi. Specifically, it mentions the four right exertions

and the four foundations of mindfulness.

Meanwhile, we learn from the Mahāassapurasutta that right effort itself is to find its expression in the practice of wakefulness –a practice of cleaning of mind of obstructive states– and the cultivation of mindfulness. Mindfulness here takes the specific form of a clear comprehension of all bodily activity.

With wakefulnes and mindfulness we may overcome the five hinderances. Once they are overcome, delight (pāmojja) and joy (pīti) arise, followed by tranquility (passaddhi) and happiness (sukha) may arise, which naturally leads to samādhi.

The discourses and commentaries underscore the indispensability of samādhi for developing insight and achieving enlightenment. This is reflected in the various classifications of samādhi related to the noble eightfold path, the roads to power (iddhipada), and the factors of awakening (bojjhanga), each highlighting different aspects and benefits of samādhi, including the potential for developing supernormal powers.

Its inclusion in the noble eightfold path as right concentration, underscores its essential role in the pursuit of awakening. While the depth of jhāna attainment required for achieving various stages of enlightenment is a subject of discussion, the texts suggest that even preliminary forms of samādhi can be instrumental in overcoming hindrances and realizing key stages on the path to awakening.

Leave a comment