“[T]xai means something akin to “brother-in-law.” It refers to a man’s real or possible brothers-in-law, and, when used as a friendly vocative to speak to non-Cashinahua outsiders, the implication is that the latter are kinds of affines. Moreover, I explained that one does not need to be a friend to be txai. It suffices to be an outsider, or even—and even better—an enemy”. [1]

Whereas our common way of thinking presupposes that to relate is to assimilate, unify, and identify, what if we inhabited a world, an ontology, where difference, rather than identity, is the principle of relationality? Such that I could receive you, a stranger, as txai, cross-cousin or brother in law, and rest in your difference –as opposed to our commonalities– as that which wards off an indifference towards you? How do I inhabit encounters in such a world? How do I receive your meaning and my meaning, and communication across both?

Controlled equivocation is a methodological approach in anthropology developed by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, a prominent Brazilian anthropologist known for his work with indigenous Amazonian cultures and his efforts to clarify why so many have misunderstood their ontologies historically, and to ultimately theorize the challenges of cross-cultural, cross-niche, cross-ontology etc understanding and translation in general.

At its core, controlled equivocation is an approach to dealing with the inevitable misunderstandings and misconceptions that arise when anthropologists attempt to translate concepts between radically different cultural contexts. Rather than viewing these misunderstandings as obstacles to be overcome, Viveiros de Castro proposes that they should be embraced and analyzed as productive sites of anthropological insight.

The method involves carefully examining the differences in meaning and reference that emerge when seemingly equivalent terms or concepts are translated between cultures. Instead of trying to find a common ground or universal reference point, controlled equivocation aims to elucidate the different ontological assumptions and “worlds” that underlie these concepts in different cultures. As he himself describes the Amerindian perspectivism found in the amazon, one “supposes a constant epistemology and variable ontologies, the same representations and other objects, a single meaning and multiple referents”.[2]

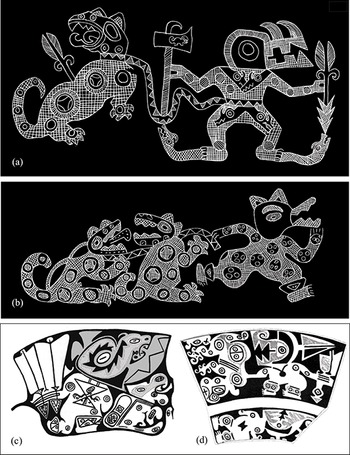

Different types of beings inhabit different but equally real “natures” or worlds. Amerindian ontologies presuppose a comparison between the ways different kinds of bodies “naturally” experience the world as a result of their “affectual multiplicity” –that is to say, as infinite rainbow of individuations of worlds within the same universe of actors taken as objects. This individuation proceed by way of the set of unique qualities, states, faculties, habitats etc of sentient bodies. Controlled equivocation is thus a method for navigating between these different realities without reducing them to mere cultural variations on a single, objective reality. Retelling a myth Viveiros de Castro is fond of, when a human protagonist gets lost in the forest and arrives at a village whose dwellers invite him to a gourd of ‘manioc beer,’ only to see him horrified when they serve him a gourd brimming with human blood, the horror only arises because the protagonist has not yet realized he’d dinning with jaguars taking human form. This inversion of sorts from dominant epistemologies that has been stewing in my mind for about 15 years.

Formalizing Controlled Equivocation in Logic

Ok so maybe you’ve gotten a taste of what this is getting at. I’ll now move on to how we might formalize controlled equivocation in terms of formal logic, abstracting it from its anthropological origins so that people like us txai can make use of it.

Basic Formalization

We’ll define two distinct logical systems, A and B, each with their own:

- Sets of primitive terms (T_A and T_B)

- Rules of inference (R_A and R_B)

- Truth conditions (C_A and C_B)

Controlled equivocation recognizes that when we attempt to translate a term t_a ∈ T_A into system B, we’re not simply finding an equivalent t_b ∈ T_B. Instead, we’re creating a mapping function M: T_A → T_B that preserves some relations while necessarily distorting others.

The “equivocation” occurs because:

- The term t_a in system A has relations r_a1, r_a2, … r_an to other terms in T_A

- The mapped term M(t_a) = t_b in system B has relations r_b1, r_b2, … r_bm to terms in T_B

- The sets {r_a1, r_a2, … r_an} and {r_b1, r_b2, … r_bm} are not isomorphic

So.. we might express a controlled equivocation relation as:

CE(t_a, t_b) = (S, D)

Where:

- t_a is a term in system A

- t_b is a term in system B

- S is the set of shared logical properties between t_a and t_b

- D is the set of divergent logical properties

The “control” aspect comes from explicitly tracking both S and D, rather than pretending D is empty.

Some initial thoughts extracting its logic this way

- Translation between systems is necessarily a partial function, not a bijection. Some concepts in system A have no meaningful mapping in system B and vice versa.

- Terms that sound or appear similar across systems (homoiophonic terms) may have completely different logical roles (homonymy). For example, the term “nature” in Western thought and “naturaleza” in Amazonian thought are homoiophonic but homonymous.

- Instead of a correspondence theory of translation, controlled equivocation employs what we might call a “difference logic” – a way of reasoning about the systematic differences between logical systems.

- Controlled equivocation requires operating at a meta-logical level that acknowledges the impossibility of a perfect translation while still allowing communication to proceed.

Practical Implementation

My interest in this idea came from what I see as fruitful practical implications of it, but at a certain level I fear it may be simply pissing in the wind with respect to how modern day conjunction of nation-states are moving. Well maybe I’ll set my sights not so much on that ur-set of txai but the one or two people that will mistakenly stumble across this blog.

In a practical logical system implementing controlled equivocation:

- We would need a meta-language to discuss the differences between systems A and B.

- Translation would be represented not as equivalence (t_a = t_b) but as a relation that preserves certain specified aspects while explicitly noting what is not preserved.

- The logical system would need to handle ambiguity not as a failure but as a feature that reveals ontological differences.

- We would need formal operators to track and reason about these differences rather than trying to eliminate them.

[1] Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo (2004). “Perspectival Anthropology and the Method of Controlled Equivocation”, Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 1. p. 16 DOI: https://doi.org/10.70845/2572-3626.1010

[2] Ibid. p. 6.

Leave a comment